Ollie Johnston – Animator – Penny

Ollie Johnston happens to be my favorite animator of all time. His drawings seem to flow like water and they all come from the heart. He started working for Walt Disney in the mid 1930’s and quickly became one of Walt’s greatest animators. Johnston saved one of his greatest performances for his last. The last character Johnston was lead animator on from start to finish was Penny from the The Rescuers (1977). What is truly amazing is how Johnston was able to climb into the skin of a character of the opposite sex who was about sixty years his junior.

The true beauty of animation is you can animate anything. I have consistently maintained the animators at Disney were some of the greatest actors to ever live. Even Marlon Brando had his limits yet the actors at Disney could portray anything from little wooden puppets to fire breathing dragons with just the use of a few pieces of paper and a pencil. In reality human characters were some of the hardest characters to animate. The reason being everyone knows how humans move and act, thus one wrong line with the pencil might ruin a performance and stop making the character believable to the audience.

These drawings are an example of Ollie Johnston exploring the character of Penny and her cat Rufus. Johnston wasn’t the best draftsman at the studio, but each drawing expresses an emotion which shows the essence of who Penny is. In most of the poses Johnston seems to be intentionally turning Penny away from the audience. He expresses an extremely shy young girl which makes the audience want to love her all the more. When Walt was alive he communicated to all his artists the most important thing in animating a character were the eyes. By this time in his career Johnston has become a master at expressing emotion through his character’s eyes. With the drawings where we see her eyes they become the center piece of the pose, our eyes are drawn toward her’s and it’s clear Johnston builds the rest of the pose around them.

One of the coolest things about my studies of the animators at Disney is the discovery of the different styles they brought to their animation. One of the true beauties of hand drawn animation is the ability for the artist to use the pencil in different ways in order to bring to life a unified performance. Ollie Johnston was not the only animator of Penny. Animation is long and tedious medium. In today’s studios there are literally hundreds of animators working on a film and it takes them weeks in order to get just a few seconds of animation finished. In the 1970’s there were far less animators working on a project. However, it still took a whole team of animators to bring to life most of the key characters. As the lead animator Johnston needed to figure out a way to get his crew on the same page with the character Penny. Drawing sheets like this were priceless samples for other animators to study so they could keep in mind who the character was both in terms of design and emotion.

Johnston had a very soft style of animating compared to his peers. He was known to barely “kiss” the page with his pencil. First you didn’t even know what it was he was drawing and then a beautiful creature would start to come to life. You can see the soft lines in the drawings of Penny. The only thick areas are places where Johnston is trying to find the right shape or communicate weight. There is a flow to his drawings; no harsh angles and extremely pleasing curves. Glen Kean, one of Johnston’s pupils and a great animator in his own right, said Ollie treated the pencil like it was a living thing and let it guide his hand in order to find the pose.

The reason I consider Ollie the greatest animators wasn’t because of his draftsmanship or even his mastery of the principle of animation. I consider him the best because he made me feel for his characters. His animation made me completely buy into the illusion of a life. His drawings disappeared and beautiful characters emerged. I saw characters I could laugh with, be frustrated at, and cry for. One of the most potent scenes Ollie did was with Penny. Johnston animated the performance of Penny and Rufus in the clip below. In it you see Ollie’s mastery of the medium. The performance is full of restraint. He holds poses and communicates mountains of emotion through small subtle movements. I consider it one of the best pieces of animation I have ever seen. And the magic of it all is it’s done through a few pieces of paper and a pencil.

WALL-E – Old Vs. New

With Pixar’s WALL-E director Andrew Stanton wanted to create a sort of look that made one think the movie was filmed in the 1970’s. This honestly was a tough goal to set since animated movies are not “filmed” they are shot in a computer, and to be honest there weren’t very many computers in the 70’s. Film is so loved by so many because of it’s inherent flaws. Things like lens flairs, grain in the image, and scratches on the celluloid are all technically flaws in film yet are now considered some of what makes it so special. It’s loved so much in-fact the leading edge in digital technology tries to reproduce the same kinds of “flaws” in their newest cameras. Stanton had a whole team try to reproduce the filmic look for his movie WALL-E. He even went as far as recreating actual live action footage of certain scenes they were doing in the computer so the technicians could see the difference between the imagery captured in camera with celluloid and that shot in the computer.

The story of WALL-E lends itself to this idea of bringing a classic look to a new medium. In the movie we follow an eight hundred year old robot, Wall-E, around his world where his main function is to pick up trash. Everything about Wall-E’s design and texture represents an old fashion look which is directly contrasted with his love interest, Eve. As you can see in the image above Eve has a oval design with very few mechanisms. The true magic of this relationship is how well Stanton and his team were able to make the two opposites seem so perfect for each other. You need to go no further then the scene where Wall-E introduces Eve to his home to see just how well these opposites work cinematically.

Some have called WALL-E an anti technology movie with a preachy message about saving the environment. However, I believe Andrew Stanton when he says he only went the environmental route because that’s where the story took him. His goal was not to make people hate the new and love the old. His objective was to create a story where two very different perspectives met and found balance. In fact it took something new coming into Wall-E’s life for him to find meaning. But more on that in another post.

Stanton went farther back then just the 1970’s for inspiration for his movie. He and the Pixar artists would watch old silent classics from the early 1930’s and before. They studied silent comedians such as Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and of course Charlie Chaplin. After studying these great filmmakers Stanton said he realized Pixar didn’t know anything. The idea that some of the best stories in our history were told without sophisticated special effects, flashy cameras, or sound blew the Pixar artists away. They made it their goal to recreate the magic they saw in the best silent films. In the first act of WALL-E there is hardly a line of dialogue heard. Rather, we discover Wall-E’s soul through a magnificent set of sound effects produced by Ben Burtt, who is best known for his work on the original Star Wars trilogy, and by the masterful work of all the Pixar animators who took the silent movies Stanton showed to heart.

In the end we have a movie in WALL-E that not only makes us laugh but also makes us care. We don’t care about seeing the environment around Wall-E change because of some liberal agenda, we want it to change because we get a glimpse of what “unplugging” and cherishing our world could do for the health of our personal souls. Those who think WALL-E is anti technology seem to forget the movie stars two robots. The best of Pixar is about balancing the new with the old. Pixar is known for being the leading edge in digital technology. They are famous for creating the first computer animated film in history, Toy Story (1995). However, the majority of their films are special because the technology is only there to enhance their stories. And, their stories revolve around themes that are as old as time itself.

A big debate is going on in the film industry today about the transition from film to digital technology. Celluloid is going extinct. There are fewer and fewer companies around who are able to process the film so it could be projected on the big screen. Some filmmakers, such as the famous Quentin Tarantino, have threatened to quite the film profession altogether if true “film” is taken away. The bottom line however is filmmaking is bigger than the stuff you use to shoot the picture. And as I said at the beginning of this post, the companies making cameras today have not overlooked the public’s love for the look that comes from the old classics of the 1970’s and before. Just like Wall-E and Eve, eventually the film industry will find a balance.

Art Babbitt – Animator – Goofy

Goofy happened to be one of my favorite Disney characters growing up. His easy going attitude and way of getting himself in and out of unbelievably dangerous situations always swept me up and entranced me as a kid. You can only imagine my surprise when I learned of Walt Disney’s distaste for the character. Considering him too dumb and unsophisticated Walt would often threaten to get rid of the character all together. And after the mid 1940’s Goofy did pretty much disappear. Sure, he did surface a few times in the 50’s as the middle class worker, George Geef. However, in the 50’s shorts Goofy’s charm seems to be all but gone; his easy hillbilly attitude replaced with a much more somber modern persona.

There is no doubt Goofy’s golden age was the 1930’s and early 40’s. With his endearing laugh and soft spoken speech Pinto Colvig was able to give Goofy a voice. However, the key author to the character of Goofy is animator Art Babbitt. Babbitt is a pioneer in the medium of animation for being one of the first to go into a deep analysis of each one of the characters he was animating. During the 1920’s and early 30’s most characters were created for the main objective of carrying out funny and abstract gags. Artists began to be attracted to Walt’s studio because he was diving into something more sophisticated, character animation; where the humor had just as much to do with the individual character’s personality as it had to do with action.

Art Babbitt quickly became one of Walt’s top animators in the 1930’s. Babbitt would have life drawing classes in his home and hire nude models. It’s safe to say Babbitt didn’t have a hard time filling up his house with young enthusiastic artists ready to learn more about the human anatomy. Soon enough Walt found out about the classes and called Babbitt in his office. Walt knew if it got out a bunch of Mickey Mouse artists were going to an employees home with nude models the press would have a field day. So Walt opened up the sound stage as a place to hold the drawing sessions and offered to pay for the classes. Though in their future Art Babbitt and Walt Disney would become bitter enemies, the two believed in the importance of education and study. From Babbitt’s suggestion Walt hired Don Graham (Check out my post of Walt’s letter to Graham here) to educate his artists so they could elevate the art of animation to levels no one before new were possible.

One of the techniques Babbitt pioneered was the detailed analysis of the character he was to animate. Babbitt analyzed Goofy intellectually. He wrote a whole outline of the character’s personality. A great amount of time was spent in trying to understand how Babbitt’s character’s thought and moved. When talking about Goofy’s posture Art Babbitt had this to say,

His posture is nil. His back arches the wrong way and his little stomach protrudes. His head, stomach and knees lead his body. His neck is quite long and scrawny. His knees sag and his feet are large and flat. He walks on his heels and his toes turn up. His shoulders are narrow and slope rapidly, giving the upper part of his body a thinness and making his arms seem long and heavy, though actually not drawn that way. His hands are very sensitive and expressive and though his gestures are broad, they should still reflect the gentleman. His shoes and feet are not the traditional cartoon dough feet. His arches collapsed long ago and his shoes should have a very definite character.

This is just a sample of a detailed lecture Art Babbitt gave on “The Goof”, as he refereed to him (check out the full lecture here). You can tell he put a huge amount of thought into the little details that would make Goofy act truly unique.

He has music in his heart even though it be the same tune forever

Babbitt’s quote nails the character of Goofy on the head. To an artist like Babbitt “The Goof” was more then just a cartoon character. Animators have often refereed to their animations as children. Animators spend so much time working with a piece of animation. They contemplate every single move their character makes and try to reach deep into their personal life to inform their choices. With this intimacy an artists develops a curtain amount of ownership over their characters. Yet, in the end they need to let them go. They need to stop animating and send them away for the whole world to see. This sense of intimacy is what attracts so many today to the field of animation. And Art Babbitt is one of the people we can thank for seeing this medium as the intimate art form it now is. A character most felt was just a dumb hick, Babbitt considered worthy of study and development. He was able to make The Goof into someone who had a soul, someone who captured the world’s hearts.

Personality Animation

As early as 1933 Walt Disney was looking into creating a full length animated feature. The story he was most interested in translating to the big screen was Snow White. One of Walt’s first encounters of the story came when he was in Kansas and watched the silent version in the Kansas City Convention Hall in 1917. To be honest the basic outline of Walt’s version of Snow White didn’t change much from this version. What separated his movie was not new plot twists or a heightening of the stakes. The Special ingredient Walt was able to sprinkle through all his movies, from 1937’s Snow White to when he died, was personality animation.

The scene above is a brilliant example of how Walt and his artists harnessed the personalities of their characters to drive the entertainment value of their story. The brilliance of this scene is its simplicity. Considered a throw away scene in most movies (put in only to communicate a narrative point) Walt uses this scene to drive home the dwarf’ personalities and their strong relationship to Snow White. The two narrative points we need to note are Snow White is being left alone and the dwarves are worried about the wicked queen. However, these points are communicated twenty seconds in. Walt makes the sequence memorable by having the essence of this moment be about developing character. Basically we see the same gag happen multiple times. The main entertainment comes from the dwarfs’ reactions after Snow White kisses them. To understand the genius of this scene one needs to understand why the gag doesn’t ever get old. The key is the different way each character reacts.

There were three Legends in the medium of animation assigned to animate the dwarfs. First was Fred Moore who did the animation for Doc, Sneezy, and Dopey. Moore specialized in appeal and you can see a huge amount of polish in the way Doc is animated. Doc communicates mainly through his hands and they are all over the place in this scene. Doc goes through several emotions here. He first shows his concern for Snow White. Staying with his character Doc’s train of thought takes a drastic turn when Snow White kisses him. He finds himself smitten by Snow White and needs to change his attitude once again so he can look like the tough leader of the dwarfs. Humor is sprinkled all the way through his performance and is directly drawn from the specific character of Doc. We find it funny Doc can’t complete a sentence because his mind is occupied by so many things. We also know deep down Doc is a softy even though he tries to act like the tough leader.

Moore has the comedy relief in the scene and he is able to highlight Doc, Sneezy, and Dopey’s personalities through their comedic action. Though the character of Dopey arguably has the most humorous reaction to Snow White’s kiss, he jumps through the window in order to come out and get another kiss from Snow White, I believe animators Frank Thomas and Bill Tytla show the most depth in the performances they pull out of their characters. Disney Legend Frank Thomas was considered a rookie in the realm of animation during the production of Snow White. He had just been promoted from being Fred Moore’s assistant to a full fledged animator and was given the task of bringing Bashful to life in this scene. Though it is a small performance it’s filled with what would become one of Frank Thomas’ signature traits, heart felt emotion. Frank was always looking for the extra little things that would elevate his character’s performances. When Bashful takes off his hat for Snow White he gently steps up to her while he says, “Be awful careful”, as if he is approaching his school sweetheart. And look at the way bashful handles his hat; it is as if he is trying to control all those strong emotions that come with someone who has just fallen in love. Then comes the Kiss and Bashful’s emotions seem to overflow and he lets out an endearing giggle.

After Bashful we get our first look at the tour de force performance of the scene, Grumpy. Walt gave one his best animators at the time, Bill Tytla, the job of animating Grumpy. Tytla was known for his ability to crawl inside his characters’s skin and capture the essence of who they were. Grumpy no doubt is the trickiest character to tackle in this scene because he goes through the greatest range of emotions. From the beginning I believe Walt and his team knew Grumpy would be the most difficult dwarf in Snow White to tackle because he could easily come across as just a mean hearted woman hater. However, because of Tytla’s superior supervision we were able to see the soft side of Grumpy show itself just enough to keep us rooting for him. Though Grumpy acts like he doesn’t care much for Snow White spread through out the film are moments where we see Grumpy’s true affection for this original Disney princess. By showing the little clip of Grumpy preparing his bald head for Snow White’s kiss we can tell he actually is looking forward to his short interaction with her before he goes. Grumpy’s walk away after he gets kissed is considered one of the best pieces of animation out there. He goes from a deep stubbornness to complete infatuation for Snow White within the span of a few seconds. Any aspiring animator should go over this scene frame by frame and see how Tytla communicates the inner emotions of Grumpy through the subtle eye movements and slow translation from the strong walking pose he carries at the beginning of the shot to the lovestruck dazed pose he has right before Snow White blows him a kiss. All the principles of animation Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas highlighted in their book The Illusion of Life are shown in this short clip. Tytla pulls off a stream of gags after Snow White blows Grumpy a kiss and all the gags are magnified by our understanding of the character of Grumpy and how undignified he feels after letting his guard down.

This small scene in Snow White is endearing because of the characters who inhabit it. This is one of the first times the Disney artists realized the simple power that could come from one character touching another. Snow White’s kisses communicated an evolution in the way audiences saw animation. No longer were we seeing cartoons inhabit the screen but rather living breathing characters who all acted uniquely and had engaging personalities. We see depth in the character of Grumpy. He is a man struggling with his built in prejudices and new found affection for someone who isn’t afraid to show him love. Walt never accepted the idea his artists were making a simple cartoon. Gags that would be forgotten as soon as the audience left the theater weren’t interesting to Walt. He wanted the audience to feel for his characters. In order for us to feel for the character we needed to buy into the ultimate illusion. We needed to believe the characters we were seeing on screen had feelings. They pulled the illusion off because the characters were alive to people like Fred Moore, Frank Thomas, and Bill Tytla. When Walt and his artists argued about a character’s action they were fighting for the integrity of someone they all saw as real and felt they knew personally.

We keep going back to a movie like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs because it holds characters we all have affection for. I find it interesting how many people love classics because of the actors who star in them. I hear comments like, “Any movie with John Wayne in it is a good movie” or, “Jimmy Stewart is always so relatable”. For animation few people know the artists behind characters like Jiminy Cricket from Pinocchio, Gus Gus from Cinderella, or Grumpy from Snow White. This makes these animators’ performances feel even more unique and special. You will never see a character who looks and acts just like Grumpy in any other movie then Snow White. The same can be said about the hundreds of other Disney animated characters who have inhabited the silver screen and visited our living rooms since 1937’s Snow White. Because of this ability for the animators to truly disappear into their characters the performances they create are timeless and always worth going back to.

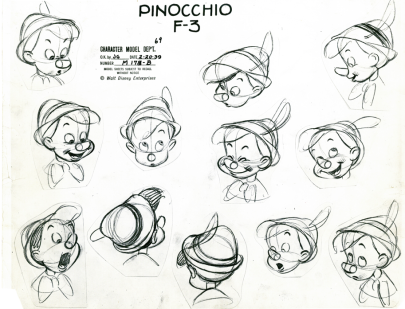

Milt Kahl – Character Designer – Pinocchio

Walt Disney’s 1940 masterpiece Pinocchio was the film where The Nine Old Men, who would be responsible for forty years Disney Animation success, first began to show their true colors. During the 1930’s and the beginning of the 40’s the main animators leading Disney animation were Bill Tytla, Fred Moore, Hamilton Luske and Norman Ferguson. These were the men who were responsible for literally defining the foundations of hand drawn animation. Disney’s now legendary Nine Old Men were but young stewards trying to gleam as much as they possibly could from these veterans. In the movie Snow White Ward Kimball was the only one of the Nine Old Men put in charge of a sequence and it ended up being dropped from the final film.

Walt Disney’s 1940 masterpiece Pinocchio was the film where The Nine Old Men, who would be responsible for forty years Disney Animation success, first began to show their true colors. During the 1930’s and the beginning of the 40’s the main animators leading Disney animation were Bill Tytla, Fred Moore, Hamilton Luske and Norman Ferguson. These were the men who were responsible for literally defining the foundations of hand drawn animation. Disney’s now legendary Nine Old Men were but young stewards trying to gleam as much as they possibly could from these veterans. In the movie Snow White Ward Kimball was the only one of the Nine Old Men put in charge of a sequence and it ended up being dropped from the final film.

During the production of Pinocchio many of Walt’s young artists saw it as an opportunity to shine. Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas did a tremendous amount of animation on the main character Pinocchio, including much of the sequence where Geppetto is controlling the lifeless Pinocchio on strings and the sequence where Pinocchio finds himself in Stromboli’s cage lying to the Blue Fairy. Since Walt understood Kimball’s devastation after having his sequence cut from Snow White he put him in charge of the character who would become the most memorable character in the movie, Jiminy Cricket. Another man who really shined during during the production of Pinocchio was Milt Kahl. Now considered maybe the greatest animator of all time, Kahl did many brilliant sequences of animation for the movie; including the little scene where Jiminy Cricket finds he is late on his first day of the job and ends up putting his cloths on while he runs past camera (I know this doesn’t sound like anything special but ask any animator about the shot and they will begin to look faint just thinking about it). However, Kahl’s greatest contribution to the movie was the final design of the title character Pinocchio.

The movie Pinocchio was actually in the works before Snow White was released in 1937. However, Walt and his artists were constantly running into a roadblock. The lead character Pinocchio was just not that likable. In fact, if you go back to the original Carlo Collodi short stories the character of Pinocchio is a cruel trouble maker who ends up killing the Cricket that Walt would appoint as Pinocchio’s conscious in his version of the story. Walt was also very put off by the original design of Pinocchio. The problem you ask? He looked too much like a puppet. The Disney artists more then anybody else at the time understood the power of having appealing designs for their main characters. The Seven Dwarfs in Snow White were filled with appealing designs. Even the never happy Grumpy was filled with curved features and a smooth movement highlighted by the great Bill Tytla. Walt understood his characters’ appeal was a huge part of the movie’s success and he was so frustrated about the lack of appeal in Pinocchio’s design he halted the project altogether.

The then nobody Milt Kahl thought he would have a go at the design of Pinocchio. He chose to treat Pinocchio not like a puppet but rather an average eight year old boy, someone would see at the local playground. Kahl came to Walt with the design you see above. The only real sign Pinocchio is a puppet comes with his nob of a nose. The round cheeks and playful looking hat gave the character a relatable innocent look. This broke through the roadblock Walt and his artists were facing and made them see the character in a completely different light. Walt realized instead of having Pinocchio get in so much trouble because he was a cruel puppet who was drawn away from humanity, he would have Pinocchio’s great flaw be a childlike naivety. Pinocchio has just come to life and thus does not know the difference between right and wrong. He is actually very human in his curiosity and is extremely impressionable. Instead of the audience being repelled by his naughtiness we are attracted by his innocence.

As I said in a prior post on Milt Kahl, 80% of the final designs of Disney characters from Pinocchio (1941) to The Rescuers (1977) were done by Kahl. Kahl wasn’t just good at designing characters because of his superior knowledge of autonomy, what makes for an appealing design, and fine draftsmanship. He was great because Walt and the rest of Kahl’s mentors installed the philosophy of creating designs where the true essence of the character could be expressed. Disney Animation has always been defined by character based animation. Through out their golden age (1937-42) and rough periods of animation (1966-82) the thing that always shined through were the memorable characters who occupied the great and not-so-great stories in the Disney films. And this is why the movies are almost all worth going back to. Little did we know at the time but with the movie Pinocchio we were watching some of the greatest actors to ever put pencil to paper come to center stage.

Joe Ranft: Part 3: A Friend and Mentor

This third and final part of my Joe Ranft series is to explain why Joe is one of the greatest influences in the history of animation. As I have explained in my last two blogs about Joe (here is Part 1 and Part 2), he went through many struggles and was able to push through them to become a very good artist. His special touch is seen through all the films he has worked on. However, what inspires me the most about Joe is not all the struggles he was able to overcome. Nor was it the magnificent art he was able to produce. Joe’s true gift was in his ability to affect those around him. His influence on film was limited to his own skill with a pencil or even the time he had on this earth. Joe had a quality that lasts even through death. Joe Ranft was a friend and a mentor to all those he worked with and because of this he will never be forgotten and he will never stop influencing the world through the people who were influenced by him.

This third and final part of my Joe Ranft series is to explain why Joe is one of the greatest influences in the history of animation. As I have explained in my last two blogs about Joe (here is Part 1 and Part 2), he went through many struggles and was able to push through them to become a very good artist. His special touch is seen through all the films he has worked on. However, what inspires me the most about Joe is not all the struggles he was able to overcome. Nor was it the magnificent art he was able to produce. Joe’s true gift was in his ability to affect those around him. His influence on film was limited to his own skill with a pencil or even the time he had on this earth. Joe had a quality that lasts even through death. Joe Ranft was a friend and a mentor to all those he worked with and because of this he will never be forgotten and he will never stop influencing the world through the people who were influenced by him.

Joe was moved by the teachers he had in CalArts. He was not only influenced to create great art from them, but also to spread the ability to do art to others. The goel was always to find the best idea possible and to do that Joe would involve everyone around him. He was far from being a solo man like his idol Bill Pete. He liked working as a team and was always open to new ideas no matter who the idea came from. Joe thought if diverse artists could work together without killing each other they could accomplish great things.

In 1987 Joe returned to CalArts to teach storyboarding. Two students Joe influenced the most was Brenda Chapman and Pete Docter. Pete Docter is now a director at Pixar and was the visionary behind both Pixar’s Monsters Inc. and Up. Brenda is now known as one of the great storyboard artists of her generation and she helped co-direct Dreamworks The Prince of Egypt. In John Canemaker’s book Two Guys Named Joe, Brenda said, “I would not be who I am, what I am, if it were not for Joe,” (page. 50).

Joe seemed to be a natural teacher. He made his students study Chaplin and Keaton films, and really concentrated on how to communicate ideas and story points through body language and the physical expression of emotions. The “meaning of the pose” was always important to Joe so he taught his students how to stage their drawings and think deeply about the pose being created so they could communicate as much as they could with their drawings. Here are a few of Joe’s rules on storyboarding from the book Two Guys Named Joe (Page 50):

- Show rather then tell.

- Communicate one idea at a time.

- Stage it so the audience can see it clearly.

- Clarity In the shot composition.

- Clarity in staging the acting or pantomime

- The Story drawing’s idea is to communicate: an idea feeling/emotion, mood, an action

- Imply animation in your drawings (through caricature, use of animation principles, I.e., stretch and squash exaggeration, etc.)

- Imagine ourselves in our character’s shoes/place.

- Leave an impression, an impact (Visual and emotional) That effects the viewer.

These were all rules Joe pounded into his students. He wanted each one of his students to be the best storyboard artist they could be. The students always had someone to talk to in Joe. He was always there to talk about an idea or way to go about telling their story. He was known for being able to deal with anyone. Unlike so many teachers today, Joe did not force his way of thinking onto his students. Rather, he helped them develop their own way of telling a story.

When Joe went to Pixar and became head of story for Toy Story and A Bugs Life he became a leader everyone looked up to, including the directors of the films he was working on. He was the first man to show up and the last person to leave. After A Bugs Life Joe took a step down from the leadership position to become more of a mentor to the Pixar studio. In their most desperate hours Joe was able to help guide first time directors like Pete Docter on Monster’s Inc and Andrew Stanton for Finding Nemo. Joe was able to crack the sequence at the end of Monsters Inc. where the main protagonist Sully is leaving his dear friend Boo for what he thinks will be the last time. Andrew Stanton, the director and screenwriter for both Finding Nemo and Wall-E said, “Everything I learned about storyboarding a film and rewriting scripts was with Joe Ranft on Toy Story” (Two Guys Named Joe, page 73).

The artist’s Joe took under his wing and helped mentor are now some of the most sought after people in the animation industry. Joe had a gift, a powerful gift. He was able to make others believe in themselves. Joe had a joy for life and his art form that could not help but rub off on others. However, this heart for helping others did not just stop in the field of animation.

Being successful while others suffered in the world was not comforting to Joe. He joined community outreach programs helping at prisons and in tough neighborhoods. He even helped convince Steve Jobs to donate computers to the Watts organization. Staying involved in the community was important to Joe and he stayed involved up to the day he died. He was killed in a traffic accident on his way to a retreat in Mendocino, California.

Andrew Stanton said this about Joe;

He was just a great listener. Probably the best. And he had a real sixth sense for when people needed it, even if you weren’t looking for it. And that I’ll miss more then anything else, is the random knock at the doorway and just going, ‘Ah. It’s Joe.’

Joe Ranft was a friend and mentor. He was there for others when they most needed him. Through the talent and the fame, it was Joe’s friendship everyone valued. And this is why Joe Ranft will never be forgotten. Friendship is his contribution that will never die.

(Here is a tribute to Joe Ranft, made by one of Joe’s good friends John Musker)

Joe Ranft: Part 2: A Dedicated Artist

In part 1 of my Joe Ranft series I talked about Joe Ranft’s struggles, both in his personal life and as an artist; one of Joe’s greatest struggles being his hardships at drawing. This is not to say Joe was bad at drawing. No, he actually became a very good storyboard artist. He was able to communicate an idea in the simplest way possible. Many artists claimed Joe’s drawings were deceivingly simple; he created the impression that anyone could do it. However this was not the case. Joe was good because of his constant devotion as an artist. He made up for his inability to draw complex figures through his ability to express a clear image. Like most good storyboard artists Joe was able to simplify a drawing, only leaving the bare minimum needed to get the point across to the audience. Joe’s greatest strength was what most of his drawings represented so clearly. Joe was known for putting heart into his art, a talent that is rare even among the best of artists.

In part 1 of my Joe Ranft series I talked about Joe Ranft’s struggles, both in his personal life and as an artist; one of Joe’s greatest struggles being his hardships at drawing. This is not to say Joe was bad at drawing. No, he actually became a very good storyboard artist. He was able to communicate an idea in the simplest way possible. Many artists claimed Joe’s drawings were deceivingly simple; he created the impression that anyone could do it. However this was not the case. Joe was good because of his constant devotion as an artist. He made up for his inability to draw complex figures through his ability to express a clear image. Like most good storyboard artists Joe was able to simplify a drawing, only leaving the bare minimum needed to get the point across to the audience. Joe’s greatest strength was what most of his drawings represented so clearly. Joe was known for putting heart into his art, a talent that is rare even among the best of artists.

During his first years at CalArts Joe tried to make up for his weaknesses in draftsmanship by attempting to copy other students styles. T. Hee (a professor and mentor to Joe) kept pushing Joe to express himself through his drawings. T. Hee encouraged Joe along with the rest of his students to figure out their own unique ways of expressing themselves and their ideas. Joe began to run with T. Hee’s philosophy and created some very unique pieces of work as an animation student. He created a short called Good Humor, where a blob of ice cream comes to life and tries to persuade a human not to eat him. Joe tried very hard to think outside the box. He often hung out with the experimental animation students trying to use them and their unique ways of thinking to push him to think of story ideas so he could push the medium of animation and storytelling to whole new level.

Joe began to find inspiration, both in the art profession and in the world he lived in. The professors at CalArts claimed the greatest tool any artist could have is their own unique experiences in life. The professors tried to push their students to experience life outside their art form. Joe was encouraged by T. Hee to take different routes to work every day and to never get caught up in a formula either inside his personal life or animation. Joe also found inspiration from the storyboard artist Bill Peet. Peet was one of Disney’s greatest storyboard artist, working for Disney from the late 1930’s through the 1960’s. He had a magnificent energy in his drawings. They expressed the action perfectly and inspired great pieces of animation. Joe knew what kind of storyboard artist he wanted to be after seeing some of Bill’s storyboard work for the movie Song of the South ( 1946). Joe could see how the drawings created the world of the movie and were full of character personality. Animators often said about both Joe and Peet’s work that the illustrations lead themselves to animation. The staging and action were so clearly expressed the drawings made the animators job simpler in a way.

Unlike Bill Peet, who was known to be a solo storyboard artist, Joe was huge on teamwork. Joe loved bouncing ideas off others and strengthening story through the combined efforts of artists working together to chisel away the unneeded parts of a story until they created a perfect piece of art. The friendships Joe created in CalArts, with artists such as John Lasseter, Tim Burton, John Musker, and Ron Clemens benefited Joe tremendously later in his career. Joe helped storyboard films such as The Great Mouse Detective and The Little Mermaid, for John and Ron. He helped create and storyboard the masterpiece The Nightmare Before Christmas with Tim Burton. And Joe created a powerful friendship with John Lasseter and was asked by John to be head of story on his directorial debut Toy Story, for the up and coming animation studio Pixar. Because of the huge success of Toy Story and his great relationship with John Lasseter Joe never left Pixar. He became head of story for Pixar’s next movie A Bug’s Life and was a major contributor to every film Pixar created from that point until his death in 2005.

Many of Joe’s storyboards had a tendency of being so strong they stayed the same all the way through a films production. For Toy Story, a movie that went through several revisions, Joe boarded a sequence where a bunch of green toy army men go out to spy on a birthday party going on downstairs. This sequence is magical and was hardly changed through out the entire production. The army men sequence also established the whole idea to what everyone wanted the film to be about – where toys come to life and think their job is to observe human life without ever being caught moving.

Joe had a mind of a student through out his life. He was constantly working on his drawing and communication skills. Joe pushed himself to become a better storyboard artist in every way possible. He believed a storyboard artist needed to have a whole slew of abilities to do their job well. They needed to be good draftsmen. They needed to know how to use and move a camera and how to compose a shot. They needed to know the basics to animations, meaning the ability to do squash and stretch, how to stage action, an understanding of timing, etc. Joe was a student of the performance and he took several classes on acting. Joe wanted to create feeling in his drawings. He wanted to provoke emotions that made the audience feel affection for his characters and the animator want to animate his drawings. Joe talked about being most at home when he was trying figure out a character. This seemed to be the reason why he was a storyboard artist; to figure out these characters who are not real in reality but real in the artist’s and audiences’ minds.

I have learned a lot from Joe Ranft’s devotion toward his art form. His example brought out the best from those around him. Joe was a very humble man, he just wanted to create the best film possible. He had a servant’s heart. He helped many first time directors, including Pete Doctor (Director of Monsters Inc. and UP) and Andrew Stanton (Director of Finding Nemo and WALL-E), become the great artists they are today. It was not a vast amount of talent that made Joe a great artist it was his passion. A passion that only got stronger through struggle and hardships. And it was this passion for the great medium of animation he was able to spread to those around him.

(To Be Concluded…)

Joe Ranft:Part 1: A Man with Many Struggles

Joe Ranft was a Pixar storyboard artist who struggled at drawing. He didn’t look like anything special. In high School Joe kept his head down and struggled to pass his classes. He was tall, over weight for his age, and quite shy. Through most of his life Joe was swimming against the tide and he never got along with authority. In fact, he was kicked out of his conservative Catholic school because he would do things like throw cat’s on the roof, never stay quite in class, and spit at the nuns who were trying to control him.

I find it amazing Joe ever became an artist at such a prestigious studio like Pixar, let alone known by one of the studios founders, John Lasseter, as being “the heart and soul of Pixar“. Most of his colegues claim Joe represented the foundations of what the studio stands for. Joe was more then a story board artist to the Pixar family; he was considered a mentor, a guide, and a prime example of what the studio embraced when it came to art and story. Before I go into the success Joe had as an artist – and more importantly as a friend and mentor – I want to look at some of the struggles in Joe’s life and what I have learned from those struggles.

After getting thrown out of his conservative Catholic school Joe struggled in public school. Today Joe may have been diagnosed with ADD (attention deficit disorder). However back when Joe was a kid they did not have categories for kids like Joe other to say they were “trouble makers” and should be “disciplined”. In sixth grade Joe entered a piece of art in a calendar contest and won. After this Joe made up his mind he wanted to become an artist. Joe applied to CalArt’s and got into their animation program.

CalArt’s was a school devoted to all aspects of art. The collage was founded by Walt Disney and many old Disney artist came out of retirement to help teach the students in the techniques of painting, drawing, story boarding, and animating. Joe Ranft became close friends with many of his professors. One particular professor, T. Hee, was of great influence to Joe..T. Hee was an old Disney story man and director. He taught caricature and storyboarding. T. Hee always pushed Joe to do things in his own unique way. When ever Joe was trying to copy another student’s art T. Hee would stop him and tell this insecure student he was interested in what Joe had to say as an individual. T. Hee was one of the first to give Joe a voice as an artist.

Unfortunately, when Joe went to Disney it seemed the studio tried to do everything in their power to muffle Joe’s voice. Joe was considered a very talented storyboard artist when he came out of CalArts, however he was put onto very mediocre projects. The CalArts students wanted to create new and unique films at Disney, the management however wanted to play it safe. This meant more of the same. After being completely denied when showing management several months of work he had done for The Great Mouse Detective and being put on the sequel to The Rescuers (a movie Joe felt was geared toward money rather then the people) Joe began to feel burnt out. He ended up leaving Disney to find a more potent means of expressing himself.

Joe had a dark side he expressed most vividly as an adult in his art work. Many of Joe’s personal pieces of art are filled with characters and descriptions I personally find unpleasant and belittling. He produced drawings of scary monsters and people with forks and knifes stuck in their heads (or sometimes through their heads). Joe used rusty red blood looking colors and smeared them on all of the character’s faces and clothes to make them look even more gruesome. He made drawings of figures with their heads cut off, distorted faces showing just as much skull as flesh, and drawings of monsters eating little innocent kids. Although with many of these drawings people could see humor I feel they revealed a great amount of insecurity in Joe and a sadness in his life he had a hard time expressing even to his closest friends.

I wasn’t surprised when I found out Joe was said to have suffered from depression through most of his life. His depression might even have thickened due to his dedication to his art form. When Joe came back to animation and began working for Pixar, he wanted to be the best leader he could possibly be for those to whom were under him. However, this meant many long hours at work. He was unwilling to leave his colleagues behind; he was the first to show up in the morning and last to leave. When Joe was head of story for Toy Story and A Bugs Life he got very little sleep and his family hardly saw him.

Thankfully Joe eventually received treatment for his depression and began to take time off to spend with his family. He stepped down from the head of story role for a while and became a mentor to his fellow artists (something I will be talking about in my next few blogs).

While on a spiritual retreat, Joe got in a freak car accident and died. He was only 45. The death was no doubt devastating to both his immediate family and his Pixar family. The good news is Joe’s struggles had a silver lining. His struggles did not consume him. Rather, he pushed through and was overcoming them all the way up to his death.

The reason why I concentrate on Joe’s struggles in this blog is because it is something we all go through as artist and as human beings. Joe somehow managed to push through the hardships and experience life. He did not only experience life, he also gave it. Joe was a man with many struggles, but he did not struggle in vain. He was able to use those struggles to create in himself an artist and a mentor who will never be forgotten in the medium of animation.

(To Be Continued…)

leave a comment