The Piano – Scene Study – The Beach

Jane Campion’s The Piano (1993) is a dark and complex tale which had a hard time connecting with a broad audience. I however found the film to be full of interesting dynamics. The film was also beautifully shot. I especially appreciate director/writer Jane Campion’s unwillingness to simplify the narrative in order to be more politically correct. In essence we are given a love story without a prince charming. There are two men who fight for the main character Ada’s affection and both characters are full of flaws and bring to the for front the kind of sexism woman have struggled with since the beginning of humanity.

The Piano was chock full of wonderful scenes where the visuals were constantly used communicate narrative and emotional points. I wanted to concentrate on one of the scenes I believe best expresses just how much meaning Campion was able to imbue into each one of her shots.

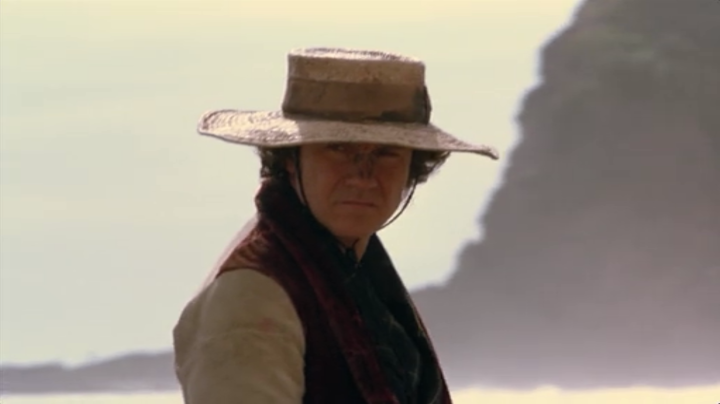

This scene takes place during the transition from the first act of the movie to the second. The main character Ada and her daughter are able to convince George Baines to go back to the beach so she can play her piano. George is falling in love with Ada despite her already being married. It’s here where we truly get a feel of George’s affection and begin to understand just how much the piano means to the story.

We first have this master shot with music playing in the background. The shot starts out with Ada and her daughter Flora walking from screen right to the piano. The emphasis is put on Ada’s need to play the piano. However, a second or two later George walks into frame connecting him to Ada and her piano. I think it would be easy to compare George to the rock on the horizon line; an object that is quite distant from the mind of Ada at the moment.

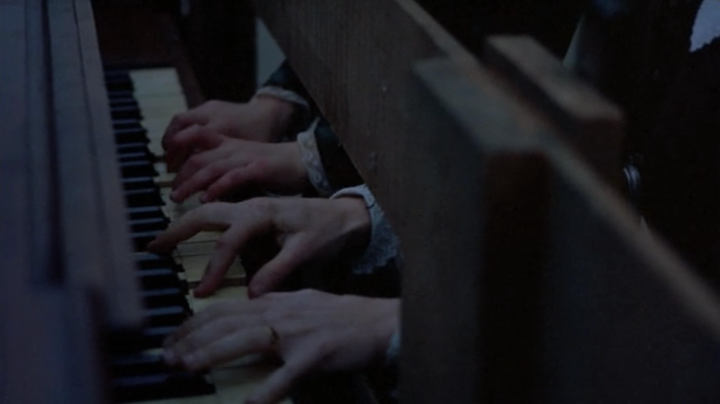

The second shot is a pan starting first on the piano and then quickly revealing Ada playing the music we have been hearing in the background. This of course directly links the piano to Ada. Also the close up of the hands is a key element; making a point that the hands are what is making such beautiful music. Ada’s hands become a crucial plot point in the third act of the movie and they already being set up here. By having this be the second shot after the master Campion is communicating Ada’s playing is the focus point of the scene.

This is part of the same pan shot. Campion is directly connects George to Ada and her piano playing. This is one of the first shots showing George’s obsession of Ada and the piano. It helps to set up the idea of him wanting her to play for him later in the movie.

The pan cuts to a close of Ada alone. It is key that the shot starts alone because it gives clarity to exactly what George is looking at. However, shortly after we see Ada’s daughter Flora run into frame and hug her mom. This moment represents Ada at her happiest. A long time goes by before we see her close to as fulfilled as we see her here.

This cut of the daughter dancing expresses the spiritual connection between Ada’s music to her daughter. Jane Campion holds the shot for a good amount of time, trying to show how in-sink the two are at this point in the story.

We have this cut to medium close up of George who in his own way is going with the music. The key is to show how Ada’s music is effecting George emotionally.

This is one of the most interesting shots of the scene. Campion breaks the rule of thirds and frames Ada so the head is in the middle of frame. This is a wonderful example of a closed frame; nothing is important but what we are seeing in frame. The shallow focus stops the background from interfering in the shot; Campion wants us to only be seeing how Ada is reacting to the music. The rest of the world and all other sounds have faded away.

I show two frames from this shot because the action inside the shot is what is really important. We first get this look from George as if he is entranced with the way Ada is being moved by her music. However, by turning his back George is in a sense denying that allure.

Yet, in the end he turns back, unable to resist his need to see Ada playing. This is a wonderful foreshadow of what is to come between Ada and George.

Here is another close up of Ada’s hands. Again, driving home the idea Ada’s hands are what are giving us this powerful music. The other important factor is seeing Flora playing with Ada. Right now in the story the two are working together, both are being physically and emotionally connected to each other with this shot.

This is from the same shot, Campion goes all the way from the close up of both Ada and Flora playing to this wide where we get a feeling of a sort of distance between the two characters. I feel like Campion is making a comment about things to come.

This last god’s eye point of view shot might be the most telling of the whole scene. It expresses the journey of the story. We first have Ada walking her own path. Flora quickly fallows and George contemplates for several long seconds before he chooses to follow suit. The shot is communicating whose story this is and the rout of some of the main characters who end up going on the journey with her.

Personality Animation

As early as 1933 Walt Disney was looking into creating a full length animated feature. The story he was most interested in translating to the big screen was Snow White. One of Walt’s first encounters of the story came when he was in Kansas and watched the silent version in the Kansas City Convention Hall in 1917. To be honest the basic outline of Walt’s version of Snow White didn’t change much from this version. What separated his movie was not new plot twists or a heightening of the stakes. The Special ingredient Walt was able to sprinkle through all his movies, from 1937’s Snow White to when he died, was personality animation.

The scene above is a brilliant example of how Walt and his artists harnessed the personalities of their characters to drive the entertainment value of their story. The brilliance of this scene is its simplicity. Considered a throw away scene in most movies (put in only to communicate a narrative point) Walt uses this scene to drive home the dwarf’ personalities and their strong relationship to Snow White. The two narrative points we need to note are Snow White is being left alone and the dwarves are worried about the wicked queen. However, these points are communicated twenty seconds in. Walt makes the sequence memorable by having the essence of this moment be about developing character. Basically we see the same gag happen multiple times. The main entertainment comes from the dwarfs’ reactions after Snow White kisses them. To understand the genius of this scene one needs to understand why the gag doesn’t ever get old. The key is the different way each character reacts.

There were three Legends in the medium of animation assigned to animate the dwarfs. First was Fred Moore who did the animation for Doc, Sneezy, and Dopey. Moore specialized in appeal and you can see a huge amount of polish in the way Doc is animated. Doc communicates mainly through his hands and they are all over the place in this scene. Doc goes through several emotions here. He first shows his concern for Snow White. Staying with his character Doc’s train of thought takes a drastic turn when Snow White kisses him. He finds himself smitten by Snow White and needs to change his attitude once again so he can look like the tough leader of the dwarfs. Humor is sprinkled all the way through his performance and is directly drawn from the specific character of Doc. We find it funny Doc can’t complete a sentence because his mind is occupied by so many things. We also know deep down Doc is a softy even though he tries to act like the tough leader.

Moore has the comedy relief in the scene and he is able to highlight Doc, Sneezy, and Dopey’s personalities through their comedic action. Though the character of Dopey arguably has the most humorous reaction to Snow White’s kiss, he jumps through the window in order to come out and get another kiss from Snow White, I believe animators Frank Thomas and Bill Tytla show the most depth in the performances they pull out of their characters. Disney Legend Frank Thomas was considered a rookie in the realm of animation during the production of Snow White. He had just been promoted from being Fred Moore’s assistant to a full fledged animator and was given the task of bringing Bashful to life in this scene. Though it is a small performance it’s filled with what would become one of Frank Thomas’ signature traits, heart felt emotion. Frank was always looking for the extra little things that would elevate his character’s performances. When Bashful takes off his hat for Snow White he gently steps up to her while he says, “Be awful careful”, as if he is approaching his school sweetheart. And look at the way bashful handles his hat; it is as if he is trying to control all those strong emotions that come with someone who has just fallen in love. Then comes the Kiss and Bashful’s emotions seem to overflow and he lets out an endearing giggle.

After Bashful we get our first look at the tour de force performance of the scene, Grumpy. Walt gave one his best animators at the time, Bill Tytla, the job of animating Grumpy. Tytla was known for his ability to crawl inside his characters’s skin and capture the essence of who they were. Grumpy no doubt is the trickiest character to tackle in this scene because he goes through the greatest range of emotions. From the beginning I believe Walt and his team knew Grumpy would be the most difficult dwarf in Snow White to tackle because he could easily come across as just a mean hearted woman hater. However, because of Tytla’s superior supervision we were able to see the soft side of Grumpy show itself just enough to keep us rooting for him. Though Grumpy acts like he doesn’t care much for Snow White spread through out the film are moments where we see Grumpy’s true affection for this original Disney princess. By showing the little clip of Grumpy preparing his bald head for Snow White’s kiss we can tell he actually is looking forward to his short interaction with her before he goes. Grumpy’s walk away after he gets kissed is considered one of the best pieces of animation out there. He goes from a deep stubbornness to complete infatuation for Snow White within the span of a few seconds. Any aspiring animator should go over this scene frame by frame and see how Tytla communicates the inner emotions of Grumpy through the subtle eye movements and slow translation from the strong walking pose he carries at the beginning of the shot to the lovestruck dazed pose he has right before Snow White blows him a kiss. All the principles of animation Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas highlighted in their book The Illusion of Life are shown in this short clip. Tytla pulls off a stream of gags after Snow White blows Grumpy a kiss and all the gags are magnified by our understanding of the character of Grumpy and how undignified he feels after letting his guard down.

This small scene in Snow White is endearing because of the characters who inhabit it. This is one of the first times the Disney artists realized the simple power that could come from one character touching another. Snow White’s kisses communicated an evolution in the way audiences saw animation. No longer were we seeing cartoons inhabit the screen but rather living breathing characters who all acted uniquely and had engaging personalities. We see depth in the character of Grumpy. He is a man struggling with his built in prejudices and new found affection for someone who isn’t afraid to show him love. Walt never accepted the idea his artists were making a simple cartoon. Gags that would be forgotten as soon as the audience left the theater weren’t interesting to Walt. He wanted the audience to feel for his characters. In order for us to feel for the character we needed to buy into the ultimate illusion. We needed to believe the characters we were seeing on screen had feelings. They pulled the illusion off because the characters were alive to people like Fred Moore, Frank Thomas, and Bill Tytla. When Walt and his artists argued about a character’s action they were fighting for the integrity of someone they all saw as real and felt they knew personally.

We keep going back to a movie like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs because it holds characters we all have affection for. I find it interesting how many people love classics because of the actors who star in them. I hear comments like, “Any movie with John Wayne in it is a good movie” or, “Jimmy Stewart is always so relatable”. For animation few people know the artists behind characters like Jiminy Cricket from Pinocchio, Gus Gus from Cinderella, or Grumpy from Snow White. This makes these animators’ performances feel even more unique and special. You will never see a character who looks and acts just like Grumpy in any other movie then Snow White. The same can be said about the hundreds of other Disney animated characters who have inhabited the silver screen and visited our living rooms since 1937’s Snow White. Because of this ability for the animators to truly disappear into their characters the performances they create are timeless and always worth going back to.

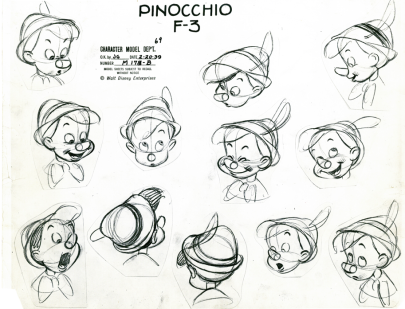

Milt Kahl – Character Designer – Pinocchio

Walt Disney’s 1940 masterpiece Pinocchio was the film where The Nine Old Men, who would be responsible for forty years Disney Animation success, first began to show their true colors. During the 1930’s and the beginning of the 40’s the main animators leading Disney animation were Bill Tytla, Fred Moore, Hamilton Luske and Norman Ferguson. These were the men who were responsible for literally defining the foundations of hand drawn animation. Disney’s now legendary Nine Old Men were but young stewards trying to gleam as much as they possibly could from these veterans. In the movie Snow White Ward Kimball was the only one of the Nine Old Men put in charge of a sequence and it ended up being dropped from the final film.

Walt Disney’s 1940 masterpiece Pinocchio was the film where The Nine Old Men, who would be responsible for forty years Disney Animation success, first began to show their true colors. During the 1930’s and the beginning of the 40’s the main animators leading Disney animation were Bill Tytla, Fred Moore, Hamilton Luske and Norman Ferguson. These were the men who were responsible for literally defining the foundations of hand drawn animation. Disney’s now legendary Nine Old Men were but young stewards trying to gleam as much as they possibly could from these veterans. In the movie Snow White Ward Kimball was the only one of the Nine Old Men put in charge of a sequence and it ended up being dropped from the final film.

During the production of Pinocchio many of Walt’s young artists saw it as an opportunity to shine. Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas did a tremendous amount of animation on the main character Pinocchio, including much of the sequence where Geppetto is controlling the lifeless Pinocchio on strings and the sequence where Pinocchio finds himself in Stromboli’s cage lying to the Blue Fairy. Since Walt understood Kimball’s devastation after having his sequence cut from Snow White he put him in charge of the character who would become the most memorable character in the movie, Jiminy Cricket. Another man who really shined during during the production of Pinocchio was Milt Kahl. Now considered maybe the greatest animator of all time, Kahl did many brilliant sequences of animation for the movie; including the little scene where Jiminy Cricket finds he is late on his first day of the job and ends up putting his cloths on while he runs past camera (I know this doesn’t sound like anything special but ask any animator about the shot and they will begin to look faint just thinking about it). However, Kahl’s greatest contribution to the movie was the final design of the title character Pinocchio.

The movie Pinocchio was actually in the works before Snow White was released in 1937. However, Walt and his artists were constantly running into a roadblock. The lead character Pinocchio was just not that likable. In fact, if you go back to the original Carlo Collodi short stories the character of Pinocchio is a cruel trouble maker who ends up killing the Cricket that Walt would appoint as Pinocchio’s conscious in his version of the story. Walt was also very put off by the original design of Pinocchio. The problem you ask? He looked too much like a puppet. The Disney artists more then anybody else at the time understood the power of having appealing designs for their main characters. The Seven Dwarfs in Snow White were filled with appealing designs. Even the never happy Grumpy was filled with curved features and a smooth movement highlighted by the great Bill Tytla. Walt understood his characters’ appeal was a huge part of the movie’s success and he was so frustrated about the lack of appeal in Pinocchio’s design he halted the project altogether.

The then nobody Milt Kahl thought he would have a go at the design of Pinocchio. He chose to treat Pinocchio not like a puppet but rather an average eight year old boy, someone would see at the local playground. Kahl came to Walt with the design you see above. The only real sign Pinocchio is a puppet comes with his nob of a nose. The round cheeks and playful looking hat gave the character a relatable innocent look. This broke through the roadblock Walt and his artists were facing and made them see the character in a completely different light. Walt realized instead of having Pinocchio get in so much trouble because he was a cruel puppet who was drawn away from humanity, he would have Pinocchio’s great flaw be a childlike naivety. Pinocchio has just come to life and thus does not know the difference between right and wrong. He is actually very human in his curiosity and is extremely impressionable. Instead of the audience being repelled by his naughtiness we are attracted by his innocence.

As I said in a prior post on Milt Kahl, 80% of the final designs of Disney characters from Pinocchio (1941) to The Rescuers (1977) were done by Kahl. Kahl wasn’t just good at designing characters because of his superior knowledge of autonomy, what makes for an appealing design, and fine draftsmanship. He was great because Walt and the rest of Kahl’s mentors installed the philosophy of creating designs where the true essence of the character could be expressed. Disney Animation has always been defined by character based animation. Through out their golden age (1937-42) and rough periods of animation (1966-82) the thing that always shined through were the memorable characters who occupied the great and not-so-great stories in the Disney films. And this is why the movies are almost all worth going back to. Little did we know at the time but with the movie Pinocchio we were watching some of the greatest actors to ever put pencil to paper come to center stage.

Tyrus Wong – Background Artist – Bambi

Center frame are two of my favorite characters in all of animation. I grew up with Bambi and Thumper. I watched Bambi (1942) dozens and dozens of times as a child and it moved me every time. This frame comes from near the beginning of the movie when Thumper and his sisters are showing the young prince around the Forrest. Not once during my childhood did I question whether or not the Forrest was real. Yet, if you really look at it the shapes making up most of the backgrounds in Bambi are but simple impressions of the real thing. As you can see in this frame the leaves, grass, and trees are void of much texture and lose almost all their detail at the edges of the frame. I personally consider Bambi to have some of the greatest backgrounds in all of animation because none of the background paintings detract from the characters and action but are able to completely transport you into the movie’s world.

Walt Disney spent a long time trying to figure out the look of the backgrounds in Bambi. With Snow White (1937) And Pinocchio (1940) Walt was much more interested in creating a look you would see in book illustration of the Brother Grimm tales. The movies were influenced by European painters from the 1800s. However, with Bambi Walt was shooting for a realism not seen before in animation. He wanted the animals in the movie to move like real animals you would see in the Forrest and so he had all kinds of Forrest animals brought into the studio to be studied by his artists in order to achieve this goal. Just look at the difference between 1937’s Snow White animals and the ones you see in Bambi, made in 1942. There is a strong attention to the anatomy of the animals in Bambi and there are only a few features exaggerated in order to have them relate more to the audience.

The animator Tyrus Wong said he never met Walt but it is clear Walt resonated with his painting style. Wong was an inbetweener animator responsible for doing the in-between drawings of finished animation in order to create the number of frames needed to have a scene move in a flawless way when played at regular speed. This was tireless and unrewarding work. Thankfully the research artist Maurice Day discovered Wong’s impressionistic paintings he had been doing on the side and brought his illustrations to Walt’s attention. Walt loved them. Not only did his impressionistic style not feel too busy, it seemed to transport Walt and the rest of the artist into the Forrest of Bambi. Wong captured the simplistic shapes within the environment of the Forrest. He also understood how light reflected off and filtered through it’s leaves and rocks. The hand drawn characters who move around in the environment had just enough detail to stick out from the backgrounds while also feeling at home in the frame.

If you look at this background painting without Bambi and the young rabbits inhabiting it, it would feel empty. The environment by itself is easy to overlook. It is made to be inhabited. I believe this should be a key philosophy for all animation backgrounds. Too often we see environments detract from the story taking place. Detail can easily become animation’s greatest enemy. The job of an animated film is not to reproduce reality but rather create just enough in order to make it feel emotionally genuine.

Tyrus Wong is still alive at age 103 and has been recognized by Walt’s daughter Diane Disney Miller and honored with a display of his work at The Walt Disney Family Museum in San Fransisco California in 2013. It is a true shame Tyrus Wong left Disney because of the 1941 strike.

Adam Kimmel – Cinematographer – Never Let Me Go

Here are a series of shots from a scene in the movie Never Let Me Go (2010) I wanted to critique. Kathy, our protagonist, just over-heard her closest friend, Ruth, and the boy she loves, Tommy, having sex and and chose to listen to a piece of music to take her mind off of what what is going on. The thing is she is listening to music Tommy gave her so we know her mind is still on Tommy. Her body language says a lot as well. She is almost hugging the tape recorder as if she wishes the take she is playing was Tommy himself. Notice how cinematographer Adam Kimmel and director Mark Romanek frame Kathy. They are using the rule of thirds, placing her eye line just at the top left third of the frame. This is known as an effective harmonizing way to frame a character. Usually the face is the center focus of a picture. If Kathy’s head was too high or there was a lot of empty space at the top of the frame the audience would be thrown off because the image wouldn’t feel balanced. Her face is lit with a nice warm light from the right. Though it is a dark scene we get the sense of peace and calmness Kathy must feel listening to Tommy’s song. Kathy opens her eyes and we cut to this next image.

Talk about a haunting image. This is Kathy’s friend Ruth standing in the doorway. Right away the eyes is thrown off because the director and cinematographer go against the rule of thirds and place Ruth’s head at the very top and too far toward the middle of frame. Yet the eyes do instantly go to Ruth. The doorway is a great framing device and the top of the dresser and the wall frames direct our eyes to her position. The filmmakers hide Ruth’s face which throws us off even more because we can’t get a good read on her emotions. The wallpaper to the right and shambled looking robe Ruth is wearing only adds to the dark mood. From this image we can tell Ruth isn’t here to befriend Kathy. She is like a dark spirit from nightmare. Lets fast forward a few shots.

Ruth has begun to talk to Kathy about how she will never be with Tommy. She is hurting Kathy at her core and the imagery reflects as much. Again the filmmakers put Kathy’s face in a much more balanced place then Ruth’s. Ruth’s face is completely in shadow and her head partly cut off at the top of the frame. The filmmakers are not afraid to work with darkness. The focus point of the image is Kathy’s eye. The light hits it just right. The eyes are the mirrors of the soul and we sense the effect Ruth’s cruel words have on Kathy emotionally. The only real color shown in the frame comes from the green wallpaper. The green compliments the toxic words spouting from Ruth’s mouth.

The filmmakers cut to this shot while Ruth is still in frame. They get closer and closer as Ruth’s words become more and more painful. But we linger on Kathy after Ruth leaves. The darkness surrounds Kathy more then ever now. We can see the effect Ruth has had on her. Again Kathy’s eyes are able to say so much. She has been completely destroyed with Ruth’s monologue.

These represent a very effective set of imagery and the music and dialogue only enhance the scene. It is a good study on the effectiveness of limiting the lighting in the scene. As good as the production might have been we don’t need to see all of it. Our eyes are allowed to focus on the important parts because the other areas are shaded. This is the darkest scene dramatically in the movie. Kimmel and Romanek want to express the darkness visually and in every shot they do so.

(Visiuals courtesy of EVEN E RICHARDS)

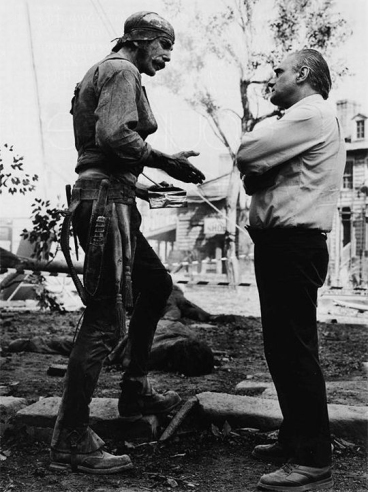

Akira Kurosawa – An Observation – The Past

One of the filmmakers I have been most reluctant to study is Akira Kurosawa. Not because he isn’t worth looking into, rather because he is considered such a legend in the great history of filmmaking. He is also the first foreign language director I have studied. The culture of Japan is much different then that of the United States. As a dyslexic who can’t read very fast it has been hard for me to watch some of his films. I hate reading subtitles because I need to pause at times and am hardly able to look up and cherish the visuals unless I do repeat viewings. However, with all these problems studying him has been completely worthwhile. Every movie I have seen is interesting. Three of his films, Ran, Red Beard and Ikiru, are among the greatest films I have ever watched.

One of the filmmakers I have been most reluctant to study is Akira Kurosawa. Not because he isn’t worth looking into, rather because he is considered such a legend in the great history of filmmaking. He is also the first foreign language director I have studied. The culture of Japan is much different then that of the United States. As a dyslexic who can’t read very fast it has been hard for me to watch some of his films. I hate reading subtitles because I need to pause at times and am hardly able to look up and cherish the visuals unless I do repeat viewings. However, with all these problems studying him has been completely worthwhile. Every movie I have seen is interesting. Three of his films, Ran, Red Beard and Ikiru, are among the greatest films I have ever watched.

Akira Kurosawa was one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. He is hailed as a master of the craft of cinema. Many filmmakers have said he is a film school in himself. They say if you want to know about film study Kurosawa. However, Kurosawa would tell you to study the world. He studied the great artists– the filmmakers, poets, and musicians– and allowed them to inform his stories and the way he told them. He also used his personal life to push his storytelling.

As with many of the filmmakers I have studied, school was not Kurosawa’s strong suite. In his biography, Something Like An Autobiography, Kurosawa described himself as too honest and rebellious in school. He said when he did something bad and the teacher asked who did it he would always raise his hand. He talked about giving snarky answers on his exams, forging papers so he could get out of activities, and messing around with dynamite in school. He never got the best grades. He never really cared enough to apply himself in school. When it came to art Akira said the teachers gave the best grade to the student who could copy something the best. He found this incredibly dull. The more I read about his childhood the more I can resonate with it. Kurosawa wasn’t the greatest athlete. He was even sent away after his third year of middle school to his older cousin’s to, as his father put it, “be cured of his physical weakness”.

Cinema was chosen by Kurosawa out of an overwhelming feeling of not belonging. His movies for the longest time concentrated on the outsider, people breaking away from the system. In Japan movies were considered extremely questionable when Kurosawa was a child in the 1910’s and 20’s. Yet, his military father took him to see many films. This was one of the few things his farther broke from tradition to do. I believe there was a tremendous strain between Akira and his father. The strain was great because Akira so badly wanted to be like him and earn his respect. Kurosawa had three sisters. He said he could relate with them way more than his older brother. He played games with them and was much more emotionally vulnerable with them then his brother and father. Akira lost one of his sisters to illness when he was in fourth grade. His autobiography reveals he had great feelings for this sister and it was a deeply painful loss.

In middle school Kurosawa began to grow up quickly. He observed the great earthquake of 1923. Though nobody close to him was killed his brother took him out to the city and both of them observed the mass damages. He said they went one place where as far as you could see there was, “every type of corpse imaginable”. Akira’s brother ended up committing suicide when Akira was in his early twenties. These things along with the great destruction of the atomic bombs in the 1940’s gives great insight to why Kurosawa’s stories so often revolve around destruction and war. Kurosawa needed to grow up quickly and he began to apply himself physically and built up an appreciation for athletics, military, and discipline.

Through the midst of all the destruction and war Kurosawa has been able to retain a powerful grip on his films emotions and the inner journey of his characters. The plots of his films are only used to dig deeper into his characters emotional conflict. This is what separates his work. Though Akira Kurosawa was forced go grow up at a very early age, he never lost touch with his emotions. This might be due to the fact he developed a relationship with his sisters. It might be due to wanting to reach out to his father. Akira said in his autobiography he believed his father was an sentimentalist at heart. One of the places where his father seemed to be willing to open himself up was in the movie theater. I can see Akira trying to reach that sentimental side of his father with his movies. I can easily say he did it with me.

The Films of Kurosawa touch on powerful inner conflicts. I am constantly stricken by how universal the themes in these conflicts are. Yet they originated from personal memories. It was Kurosawa who said, “Creation is memory”. He believed as artists we must hold on to the present and the past in order to inform our future. As with the great John Ford, in Kurosawa’s later films you see a tremendous desire to hold on to what once was. The great filmmakers have this desire because the past is where their great memories rest and where their greatest creations originate.

Joe Wright – An Observation – Telling a Story

Joe Wright is one of those filmmakers who likes to let his audience know he is telling a story. At the beginning of Pride and Prejudice the main character Elizabeth is reading a book, which Wright described as the beginning of the story she is about to go on. In Atonement the first thing we see is Briony typing out the last part of her play. At the end of the story we find out she is in fact the author of the story we are watching. The Soloist revolves around a group of articles the main character Steve Lopez wrote for his newspaper. Hanna was described by Wright as a sort of fairytale and we see Wright express this motif constantly; through the main character Hanna reading out of the Brothers Grimm book, the way Wiegler dresses in green and red to resemble a witch, and the fact the whole third act takes place in a deserted circus land which resembles something you would see in a classic fairytale. In Wright’s latest feature Anna Karenina he goes a step further in making it obvious what we are seeing is made up. He fictionalizes the story by setting it in a theater. Wright makes it obvious the actors are on the stage when performing. Instead of cutting to another scene we at times see prop men come out and change the location in front of our eyes. We even have scenes take place in the prop room, backstage, and up on the catwalks.

Joe Wright is one of those filmmakers who likes to let his audience know he is telling a story. At the beginning of Pride and Prejudice the main character Elizabeth is reading a book, which Wright described as the beginning of the story she is about to go on. In Atonement the first thing we see is Briony typing out the last part of her play. At the end of the story we find out she is in fact the author of the story we are watching. The Soloist revolves around a group of articles the main character Steve Lopez wrote for his newspaper. Hanna was described by Wright as a sort of fairytale and we see Wright express this motif constantly; through the main character Hanna reading out of the Brothers Grimm book, the way Wiegler dresses in green and red to resemble a witch, and the fact the whole third act takes place in a deserted circus land which resembles something you would see in a classic fairytale. In Wright’s latest feature Anna Karenina he goes a step further in making it obvious what we are seeing is made up. He fictionalizes the story by setting it in a theater. Wright makes it obvious the actors are on the stage when performing. Instead of cutting to another scene we at times see prop men come out and change the location in front of our eyes. We even have scenes take place in the prop room, backstage, and up on the catwalks.

If you really think about it most films have very little resemblance to real life. Even the ones based on true stories are completely manipulated in order to express a curtain view. Whether these views are of substance, accurate, or worth your time has everything to do with the storyteller. Joe Wright is a master at using the tools of cinema to manipulate the audience’s view. Wright doesn’t even try to hide this fact. He wants you to understand you are watching a story and not reality. He tells you this through the way he composes shots, uses music, and edits his films. In fact every time a filmmaker chooses to make a cut, use a curtain angle, or bring in music he is manipulating the audience’s emotions. Wright just is a master at it. His job as a filmmaker is not to tell the literal truth, it is to use the tools of manipulation he has at his disposal to tell the emotional truth of his story.

“A storyteller is someone who hides the truth in fiction so you can see it better”

Steven Parolini

This is one of the best explanations of a filmmaker’s job. We have the power to send people off to lands where gods and giants rein, to galaxy’s light years away, or to worlds that resemble ours but have toys come to life and animals talk. Wright makes no attempt to make you believe what you are seeing is real. He understands the power of the audience understanding they are watching a story. He wants to exaggerate what we see in real life and create an experience. His job is to understand the heart of his story to such a great extant he could manipulate whatever he needs in order to make the heart of his film resonate with the audience. Wright has experienced life. His films are proof of this.The heart of his stories come from a real and truthful place in his heart.

The reason films like Hanna, a story of a child trained assassin, or Pride & Prejudice, a 17th century drama, resonate with the audience is because they go beyond their genre and show universal truths. Whatever Wright thinks he needs to peel away in order to express those truths more clearly he will take away. It is why we see such impressionistic work in a movie like Anna Karenina. Wright felt the story of lust and love would work better if he heightened the surroundings. He uses extreme color schemes in order to express the emotions of the story and his characters. In the movie Wright does not waste time cutting to different scenes. He has many of the sets change in front of our eyes because his characters’ lives are in constant flux. In Wright’s films we follow his characters’ emotional arcs. The surrounding is completely changeable depending on where his characters are emotionally.

Telling a story requires a lot of talent and technique to get it right. The director needs to be thinking about the framing, music, lighting, sound design, costumes, actors, camera movement, how all those things contribute to the scene, and how the scene contributes to the whole, through out the whole filmmaking process. This takes a lot of devotion and study to get right. You will not get someone who is interested in putting in the countless hours of time and effort unless he is completely devoted to telling the story he has to tell. Joe Wright is a storyteller and his art is telling a story. No wonder he likes acknowledging this in his films from time to time. Yet, Wright doesn’t care whether you catch his acknowledgments. He actually wants you to get so interested in his worlds and so close to his characters you get completely invested in the story. He wants to reveal to you the wonders of the worlds he creates and the emotions of his characters. He wants to tell you a story you will never forget.

Joe Wright – An Observation – Responding

From my studies I have found there are two very distinct kinds of directors both of which I have tremendous respect and admiration for. There are the Fincher’s and Kubrick’s of the industry who are known for being perfectionists. Many say they already have the movie in their head before they shoot their first shot. Their job is to get what is in their head into the camera. Usually this involves countless hours of tedious work, where the director is trying to control as many details as the time allows to get his vision onto the screen. The other type of director I have encountered is the “Go with you gut” directors. These directors are the Eastwood’s and Spielberg’s of our day. Every day is a inspiration to them and they let these inspirations drive their directing. They do not obsess over flaws in the frame, in fact they capitalize on mistakes a actor makes or the weather creates and bring a more authentic feel to their films.

From my studies I have found there are two very distinct kinds of directors both of which I have tremendous respect and admiration for. There are the Fincher’s and Kubrick’s of the industry who are known for being perfectionists. Many say they already have the movie in their head before they shoot their first shot. Their job is to get what is in their head into the camera. Usually this involves countless hours of tedious work, where the director is trying to control as many details as the time allows to get his vision onto the screen. The other type of director I have encountered is the “Go with you gut” directors. These directors are the Eastwood’s and Spielberg’s of our day. Every day is a inspiration to them and they let these inspirations drive their directing. They do not obsess over flaws in the frame, in fact they capitalize on mistakes a actor makes or the weather creates and bring a more authentic feel to their films.

Joe Wright is a director who falls under the category of “go with your gut” directing. He has done his research but he relies on the performances, costumes, and locations to guide his directing. He wants to be inspired. This is one of the main reasons he does not like working on sets. No matter if he is shooting a period piece, a thriller, or a buddy movie, Wright wants to find actual locations to do most of his shooting. He get’s inspired by the locations and they become just as involved with his story as the characters. His mission is to inspire the crew and the actors to do their best work. He sets things up so the actors can actually mingle with the extras when they are not shooting. He plays music and gets rid of as many distractions as he could so his crew stays on task. During inmate scenes Wright said he tries to have only him, the sound recorder, the grip, and the cinematographer present with the actors so they could feel as comfortable as possible while executing their scene.

One thing you will notice with almost all of the personal scenes in Wright’s movies is his use of the a handheld camera or steady cam. In his commentary on Pride & Prejudice Wright talked about how most of film is about the technical part of filming but the handheld empowers the actors. The great Italian director Federico Fellini is widely known for making the handheld style of filmmaking popular for the coming of age generation in the 1970’s. The first Rocky film was a breakthrough movie with the steady cam. Through the use of the hand held and steady cams filmmakers found they were less limited with the camera and could explore more personal things and create a more realistic feel in their stories. Using handhelds and steady cams allows the camera man to react to the action on screen in a much more intimate way. Wright likes to respond to what he sees and what he feels. When we watch Wright’s brilliant multiple minute single shots in Pride & Prejudice, Hanna, and Atonement, they are successful because they allow us to take a uncut second person view of the situation and soak in the environment, characters, and story as though we were there. We feel like we are in a 17th century ball, walking in the midst of beaten down World War II soldiers, and trying to escape from secret spies, all because of Wright’s superb ability to transport us into his worlds through the intimacy of the camera.

Even music is used in many of Wright’s films through the response of natural sound effects in the environment. Atonement starts off with the main character Briony at her type writer finishing her play. The typing from Briony slowly transitions into Briony’s theme music with the type writer noise maintaining the basis of her themes beat. At the end of the first act when Robbie is taken away, his mother begins to bang on the front of the police car. The banging becomes the main beat for the powerful climatic music used to end the first act. We see a similar use of sound in the movie Hanna, where helicopter propellers, traffic sounds, and combat noise transitions into the main themes used in the Chemical Brothers score. This is just another example of how Wright is inspired by the world around him and lets it guide him even in post production.

A good directer needs to balance between being prepared and leaving room to be inspired. After watching Wright’s latest film Anna Karenina it seems he brings his response oriented directing style farther then ever before. Unlike Wright’s other films Anna Karenina is mostly shot inside a set. He wants to bring to attention the story he is telling is piece of fiction intentionally dramatized to provoke emotion. Everything seems to be a response to Anna’s emotions. There is even a time where everything stays still until Anna’s vigorous passion awakens them. Wright wants to awaken his audience . He will hit us with emotions that sometimes defy logic. In most of Wright’s films he does not even try to hide the fact we are watching a story unfold. He has no intetion in making these stories look real. Instead he wants them to feel real and he will dramatize whatever he needs to to get the desired effect. He is looking for the audience to feel anger towards his characters, love, sorrow, and happiness. In short, Wright is looking for a response.

Joe Wright – An Observation – Dyslexia

I first started to research director Joe Wright when I found out he was dyslexic. He has said in interviews his dyslexia made him feel stupid and is one of the big reasons he didn’t finish school. The man just didn’t read as fast as other students and he wasn’t a linguistic thinker. I am sure the school system was, like it is to so many other dyslexics, not kind to Mr. Wright. It is interesting however that Wright says his dyslexia is also the reason he has been so successful in the film profession. In a interview on The Telegraph Wright stated, “I think my dyslexia was a vital part of my development because my inability to read and write meant that I had to find knowledge elsewhere so I looked to the cinema”.

I first started to research director Joe Wright when I found out he was dyslexic. He has said in interviews his dyslexia made him feel stupid and is one of the big reasons he didn’t finish school. The man just didn’t read as fast as other students and he wasn’t a linguistic thinker. I am sure the school system was, like it is to so many other dyslexics, not kind to Mr. Wright. It is interesting however that Wright says his dyslexia is also the reason he has been so successful in the film profession. In a interview on The Telegraph Wright stated, “I think my dyslexia was a vital part of my development because my inability to read and write meant that I had to find knowledge elsewhere so I looked to the cinema”.

A fair question to ask is “why did Wright fail in school but find substance through the cinema?”. In order to understand you must learn a little more about dyslexia. Dyslexia is usually labeled as a learning disability. Those diagnosed with dyslexia usually have a hard time with organization, reading, writing, and spelling. The majority of school systems rely heavily on verbal and linguistic teaching creating a huge disadvantage for dyslexics. Knowing this it is easy to understand why Wright failed in the school system. However the cinema can also be a learning tool. The cinema teaches through the use of images. Through the cinema’s stories we learn lessons on politics, geography, evolution, religion, humanity, and so on.

I don’t believe Dyslexia is a learning disability. It is a different way of thinking. Dyslexics think through images. Some of the strengths associated with dyslexia are the ability to think spatially, being able to look at a problem from multiple angles, advancements in the imagination, and being able to see the big picture of any given problem or project. If you watch Joe Wright’s movies you can see how he has a firm grasp in all these areas.

When listening to Wright talk about his films it seems he relies more on instinct then any literal reasoning. He has done the research for his project but he wants to let the locations and visuals dictate the way he films. Because of this we find every frame in his movies stimulating. His main mission is to provoke emotion through his visuals. Wright never lets the details of the plot get in the way of his characters’ emotional growth. As a dyslexic myself I remember taking tests and always doing badly because I didn’t remember names and dates. What fascinated me and the things I constantly talked to my parents about were the emotions of the events I had learned about, how those impacted the people during that time period, and how they related to me in the present. I understood the material but didn’t have the ability to express my understanding through writing or the the tests I took. I can imagine Wright had a similar problems.

For Wright the literal facts seem to be the farthest from his mind. In Wright’s first feature film Pride & Prejudice he doesn’t care about the fact that Elizabeth Bennett is at a much lower class then Mr. Darcy as much as he cares about the emotional effect that fact has on their relationship. In Hanna the whole plot point of the title character Hanna being genetically altered in order to be a better killer was described by Wright as no more then a “macguffin” (a plot device with little to no explanation, used to propel the story). What mattered is this plot point propelled us into an emotional story. We see a child grow up and emotionally go to battle with what she was made to do verses what is morally right.

One of the most important things a director must be able to do is have the big picture of the film in his mind while shooting individual scenes. It has been clinically proven that dyslexics use their right brain to a much higher extant than most non-dyslexics. The right hemisphere of the brain is responsible for seeing connections that tie things together and seeing how parts relate to wholes. The beach scene in Atonement and the exploration of Skid Row in The Soloist are examples of Wright leaving the main characters entirely in order to observe the bigger picture. He is able to ground his individual stories by showing us the world around the stories.

Wright creates connections in his films in many ways, including the use of mirror imagery, musical themes, and repeating pieces of dialogue. In Hanna we see the title character use the same line of dialogue to start off the story and to end it; making us reflect on how or if the events she went on had created any change. Two of the key scenes in Atonement are when the main character Briony tells the great lie to the investigators towards the beginning of the story and the truth to the reporter at the end of the story. The lie is what sends us into the conflict the rest of the story revolves around and the truth is what resolves the story and brings the audience closure. Wright binds the two scenes by using the same framing, background, and has the main character Briony looking straight into frame both times. We instantly see how these scenes are connected and how important they are to the narrative of the story. At the beginning of Pride & Prejudice we hear the musical theme we come to associate with Elizabeth and the Bennett Family. However the same music is played by Mr. Darcy’s younger sister when Elizabeth visits Mr. Darcy’s house. Though Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy’s worlds look quite different the music unites them emotionally. Wright’s ability to understand the complete story gives him more insight on how to direct these individual scenes and connect them to the greater narrative.

No matter how much a dyslexic has worked to overcome his or her natural weaknesses the struggles are never completely resolved. Wright still says it takes him much longer to read a script or a book then most people. However he has found ways to change these perceived weaknesses into strengths. Wright has said, “Because I think visually, not being able to read meant that other parts of my brain were pushed further, and so when I read a book, I have to see it”. It is not a accident that three of the five movies Wright has directed have been based on literary classics. It’s not that Wright is against reading, very few dyslexics are. It’s just the words come to Wright’s mind as pictures. Wright’s ability to see what he is reading allows him to translate the written word to film in a much more visually expressive way.

There are many others who have struggled in the classroom to become some of the greatest filmmakers in history. It is suspected that the great filmmaker David Lean struggled with dyslexia as a child. He hardly got by in the school system and was constantly made fun of by peers and his father for being a slow learner. Steven Spielberg is another diagnosed dyslexic who also severely struggled in the school system. These filmmakers did not just overcome their dyslexia they have used it do miraculous things in the cinema. I feel Joe Wright is on his way. Many would call movies like Pride & Prejudice and Atonement some of the best films of this new century. It is hard not to call his five minute shot of the Dunkirk evacuation one of the most awe inspiring shots in all of cinema. Wright continues to explore his art form and he is going in an ambitious direction. His last two films have been criticized for being over the top and against the grain of established cinema. However “against the grain” is a perfect description of dyslexia. We think in a different way and are often called failures in the established system because of it. Still, many of these school system failures, such as Steven Spielberg, Albert Einstein, and Thomas Edison, have the greatest success stories in our history.

2 comments